By Elio Wilder (they/them)

Home ownership is increasingly out of reach for many Australians, most severely impacting young and marginalised people.

Put simply, housing supply is low and prices are high. But how and why has that come to be? And more importantly, how do we overcome it?

1) Negative gearing and capital gains tax legislation = tax discounts for the rich

Money derived from renting a property is considered income and is taxed at the owner’s marginal tax rate. If they make a loss on the investment this is deducted from their taxable income total, thereby reducing their overall tax liability. This is known as negative gearing. This is achieved by using borrowed money to purchase a property and ensuring the rent is less than the mortgage and ownership expenses. The tax discount is bigger for those in higher tax brackets, thus this method benefits higher income earners the most.

Capital gains tax is tax paid on income derived from selling an investment. Prior to June 2000, capital gains tax was calculated based on the total gain (sale price – cost price - inflation over the period of ownership). Then, the Howard government changed the legislation so capital gains tax is now only paid on a flat 50% of the gain. The other 50% is completely tax free.

Whilst other investments like stocks and bonds don’t directly lead to increased homelessness, investors can’t get the same tax discounts by putting their money in these areas. A massive tax-free pay day incentivises property investment. With investors driving up demand, property prices increase.

Solution: Transition back to pre-June 2000 capital gains tax formula

2) Transfer duty disincentivising downsizing

The majority of new builds in the most populace areas are apartments. There is very little undeveloped land remaining in metro areas for detached housing. The finite nature of this specific housing supply has seen prices consistently skyrocket. Sydney house prices rose 10.6% between December 2022-23 compared to 6.3% for units.

Houses are often owner-occupier family homes and are frequently held by the one family for 15+ years. Traditionally, when the children grow up, they move out and the parents downsize, making way for the next growing family. However, young people are living at home longer due to the unaffordability of housing and the government-imposed cost of downsizing acts as another deterrent.

Transfer duty (aka stamp duty) is tax paid on the purchase of property to the state government. It is calculated based on the sale price. Transfer duty on the median unit price of $795 000 in Sydney is over $30 000. So even a substantial downsize is likely to incur tens of thousands of dollars in transfer duty. For many empty-nesters who’ve paid off their mortgage, it’s more appealing to stay put and enjoy the extra space than sell, pay the duty, and live smaller.

Solution: Tax incentives for empty-nesters who are looking to downsize. On one hand this would reduce revenue gained from the downsizer, however it would likely increase the rate of turnover of homes, leading to an overall increase in transfer duty revenue and more chances for growing families to buy a home.

3) Occupancy rates

The 2021 Australian census revealed that more than 1 million homes (10.1% of all supply) were unoccupied on census night.

There are many valid reasons why homes may be unoccupied in the short term. The issue is properties that are vacant in the long term, particularly the practice of ‘land-banking’ where property is held until a change in circumstances (such as land-rezoning) allows the property to sell for a higher profit.

Solution: Vacant Residential Land Tax (VRLT). Since January 2018, VRLT has been in operation in Melbourne. Properties that are unoccupied for 6 months or more in the previous calendar year (without a valid exemption) attract a tax of 1% of the property’s current market value. This decreases vacancy rates and generates revenue that can be used to improve the community.

4) Rate of new builds vs population growth

In a 2023 update, the ABS reported private house approvals had reached a 10-year low, demonstrating stagnation in building.

The most recent ABS estimate states the number of dwellings in Australia increased by 1.4% of the 2021-22 financial year, bringing the total to 10.9 million. In contrast, in the 12 months preceding September 2023, Australia’s population increased by 2.5%. The 10-year median growth is 1.51%.

Every day, thousands of people arrive in Australia to settle permanently, and thousands of residents turn 22 (legal age of independence). Put simply, the population is consistently increasing at a faster rate than new dwellings are being established. This most severely impacts metro areas, where many people need to live for employment, study, and health reasons.

Solution: In addition to reducing vacancy rates, the rate of new residential development needs to increase to keep up with population growth. Particularly in metro areas near jobs, universities, and public transport.

5) Lack of appropriate housing supply

It’s not just a lack of housing supply, it’s a lack of appropriate housing supply.

The birthrate is declining as young people are increasingly likely to choose not to have children. More singles and couples are seeking studios and one bedroom properties, but the existing supply (and many new building projects) are oriented towards families with children.

The result is inefficient use of housing, evidenced by empty bedrooms. Though a spare bedroom is handy for many, there are less than 11 million total dwellings in Australia contrasted with 13 million empty bedrooms. This suggests millions of houses have multiple unoccupied bedrooms.

In NSW, there are around 210 000 one bedroom and studio properties, but more than 720 000 people live alone.

Solution: New developments should factor in the changing demographic of Australia by incorporating adequate supply of studios and one bedroom properties into their projects. These should be affordable on a single income.

6) Land zoning

Land zoning is primarily determined by the local council and specifies things such as minimum block size and how land can be used.

Minimum block size restrictions can be helpful in environmental and aesthetic conservation, but they also limit the creation of new affordable housing.

Those profiting from the housing crisis are prone to suggesting, ‘if you can’t afford the city, then leave’. Young people should not have to flee their hometowns just to have a roof over their head. And it’s far from that simple anyway.

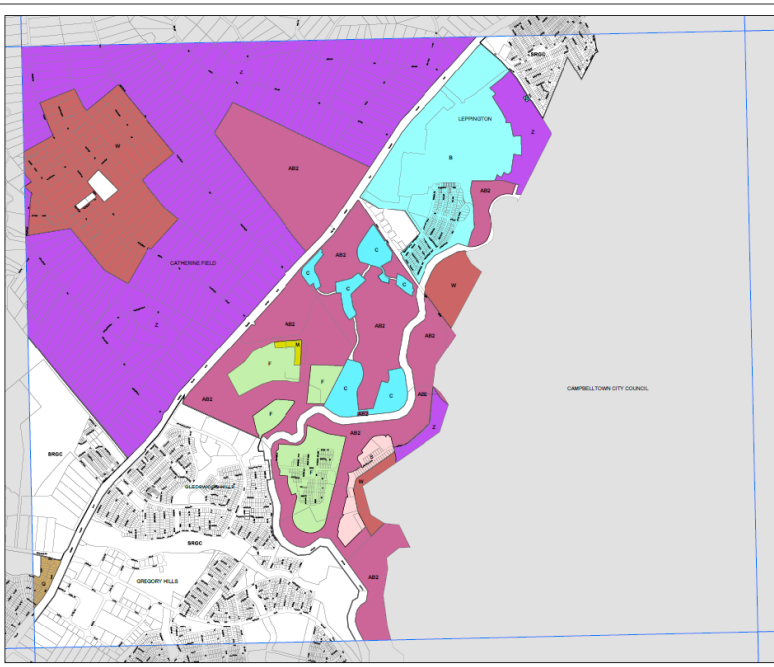

Camden Council in south west Sydney: All of the purple area is minimum block size of 2ha. Image via Camden Environmental Plan 2010

Whilst property hypothetically gets cheaper as you move away from urban centres, what more commonly happens is the property gets better value for money. Perhaps you can’t afford the $1.5m 500sqm vacant block in suburban Sydney so you look further out to the fringes, trouble is the blocks out there are $1.5m too, they’re just a lot bigger.

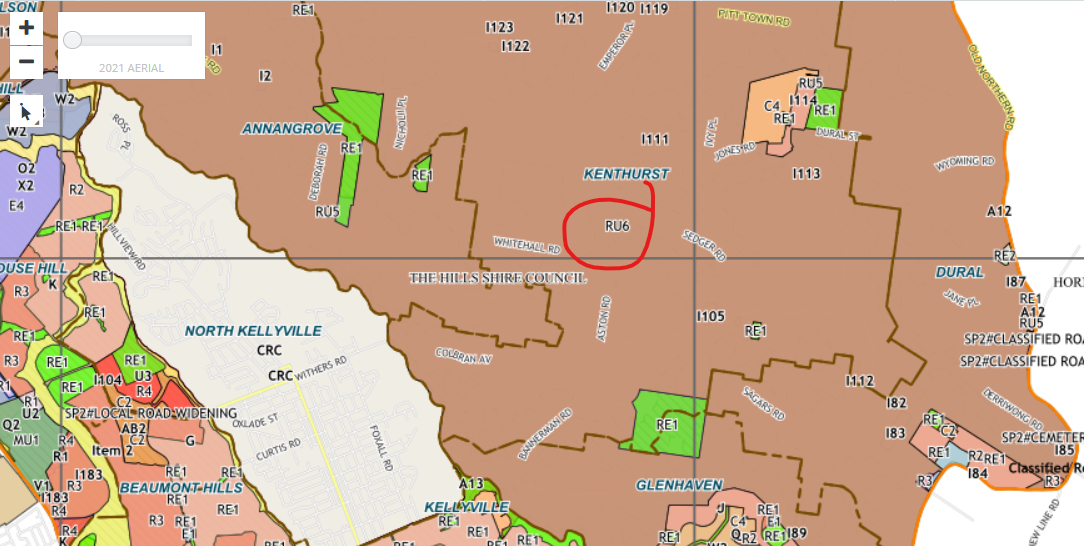

The Hills Council in north west Sydney: All of the orange/tan area is RU6 with a minimum block size of 2ha. Image via The Hills Council land zoning map

Much of the land on the fringes of Sydney is dominated by multi-million dollar acreage. Many blocks have zoning restrictions such as RU6 or RU2 which have a minimum block size of 20 000sqm. These blocks have one title, can’t be subdivided, and are only allowed one primary dwelling (and potentially a granny flat). For comparison, R2 zoning has a minimum block size of 500sqm meaning 40 detached houses with backyards could be built if a single block of semi-rural RU6/2 land was rezoned to R2.

Solution: Re-zone land in strategic locations within commutable distance to urban centres to allow for subdivision. Implement minimum green space requirements for developments to promote environmental and aesthetic conservation.

7) Housing density restrictions

In addition to restricting block size, land zoning legislation also limits the density of housing on certain blocks. This restricts (and sometimes outright bans) things like renting a small section of a rural property to park a tiny home on or converting a three-storey house into three apartments through internal subdivision.

Tiny homes offer home ownership for less than $150k. The biggest issue is finding somewhere to park it. With a lack of affordable land within commuting distance of our nation's capitals, and restrictions on land use, tiny home owners often rent land to park and live on unlawfully and live in fear of being moved on by the council. In NSW, granny flats can be built without council approval on block sizes over 450sqm, but as soon as that small dwelling is on wheels, its permanent occupation is banned.

Internal subdivision is common practice in cities such as London, with many once two-storey homes now an upstairs flat and downstairs flat with two separate titles. This gives twice the number of people the opportunity to access home ownership on the one block, with minimal impact to the visual landscape.

Solution: A few regional councils are beginning to accommodate tiny homes in their legislation and the rest should follow along. All councils should allow well-maintained tiny homes to be permanently occupied on residential land in an owned or rented capacity. Councils should also make it easier to receive approval to internally subdivide established large homes.

8) Wage growth vs house prices

Property prices have risen considerably more than wages over the past 20 years. Exactly how much is relative to where and who, with low-income earners and metro areas the most impacted. In 2001, the median dwelling price in Sydney was 5.8 times the average annual income, by 2018 that had risen to 9.3 times.

Lower incomes and higher rents increase the amount of time it takes to save a deposit. And yet, comparatively speaking, saving for the deposit is the easy part. To purchase an average priced house in Sydney, a household income of $261 000 is needed just to maintain the mortgage.

Solution: Whilst there are many ways to go about decreasing the discrepancy between wage growth and house prices, increasing the supply of housing available to first home buyers through all the aforementioned solutions on this list is a great place to start.

References

https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/109-million-dwellings-australia-june-2022

https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/national-state-and-territory-population/sep-2023

https://www.abs.gov.au/media-centre/media-releases/private-house-approvals-hit-10-year-low

https://abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/CED142

https://www.domain.com.au/research/house-price-report/december-2023/

https://www.aussie.com.au/content/dam/aussie/documents/home-loans/aussie_25_years_report.pdf

https://www.revenue.nsw.gov.au/taxes-duties-levies-royalties/transfer-duty#heading4

https://map.hornsby.nsw.gov.au/intramaps99/default.htm?project=HornsbyPublic&module=HLEP%202013

https://www.hawkesbury.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/204588/20220412AT2toItem72.pdf