"What you project is what you believe": The Politics of Women's Fashion

By Ella McKelvey - National Director of Online Engagement (Blog)

"What you project is what you believe"

Michelle Dhansinghani - President and CEO of Elan StrategiesSpeaking at 2018 Women’s Campaign School, Yale University

In 1920s France, the bobbed haircut-craze unfurled across the nation. The hairstyle was a highly controversial invention – women were snubbed, sequestered or even murdered by their families following the adoption of the hairstyle.

What made a simple haircut become the source of so much scandal?

According to Mary Roberts, author of “Samson and Delilah Revisited: The Politics of Women’s Fashion in 1920s France”, the bob haircut represented a striking contrast to the pre-war fashion of voluminous and elaborate hairstyles. It accompanied a trend in women’s clothing away from the intricate and uncomfortable, and towards the practical and liberating. The rapid changes in women’s style reflected a sudden increase in “attention to the female identity in the fictional, theoretical and periodical literature of the years 1917 to 1927” – in particular, new ideas were emerging about a women’s liberation from traditional roles, especially as mothers, and the hairstyle was symbolic of the advent of the modern young woman.

By Djuna Barnes - Arizona Republican. (Phoenix, Ariz.), 25 Sept. 1920. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress., Public Domain

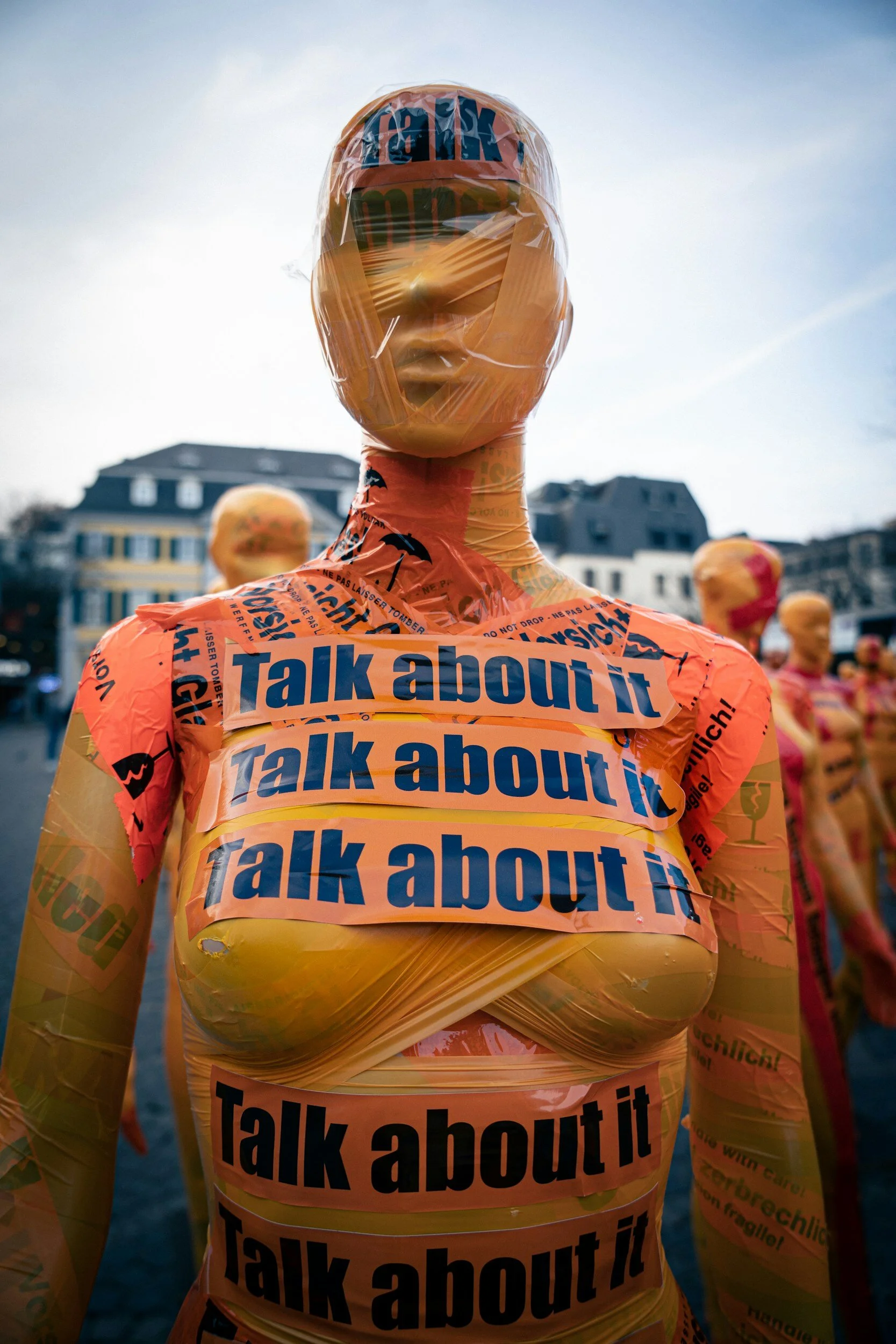

Fast forward almost 100 years to 2016 – 2019, and we are seeing yet another wave of women using their personal style choices to communicate political ideals: think celebrities wearing black in support of #MeToo at the Golden Globes, and the Planned Parenthood pins and Pussy Hats that made frequent appearances everywhere from fashion shows to Women’s Marches. Although politically-branded clothing has existed for decades, it made a resurgence following the 2016 US Presidential Elections.

Like the bob in 1920s France, these style choices have sparked both conversation (actors received international press attention for wearing planned parenthood pins to award ceremonies) and controversy (although supposedly feminist symbols, Pink Pussy hats were later criticised for being both racist and transphobic); albeit with much less extreme ramifications for the wearers.

It is easy to understand why fashion was an important political tool for women in eras past - with limited access to education and no voting rights, women had fewer opportunities to express their opinion. So, why do women in the cultural West still choose to make use of fashion for politics?

Certainly, the aesthetic qualities of clothing can make them an attention-grabbing canvas for the display of political imagery or branding. Clothes move, and they have more capacity for colour, texture and shape than posters might. On social media sites like Instagram, beauty is the currency of popularity; and so by making politics beautiful, social media can become a platform for disseminating political messaging to its hundreds of millions of users. In late 2018, for example, Beyoncé posted three photos of herself wearing a “BETO for Senate” baseball cap on her Instagram account. These photos racked up a total of 9 million likes.

Even for non-celebrities, clothing can be one of the most effective tools for promoting awareness of political causes. By carrying political messages on our bodies, we are choosing to weave them into our daily lives. We connect our presence and faces to the messages we adorn. You wouldn’t expect someone to stop your moving car to enquire about a sticker, or to knock on the door of your house because of a poster in your window, but you know there is a possibility that the person next to in the coffee line might ask about your t-shirt.

During the 1920s, the act of wearing controversial clothes/hairstyles was seen as just as rebellious as the clothes themselves. The bob haircut was as much about being practical as it was about showing an individual desire to defy social convention. Fashion has since grown much more diverse, and with there being more clothing choices available, clothing conventions are less rigid and less clearly delineated.

Nonetheless, fashion “conventions” still exist, and so clothing does not need to be branded to be political. Some items and styles of clothing are still seen as intrinsically radical. The persistence of queer fashion as a distinct style of dressing demonstrates that, even if less clearly defined than at the turn of the century, gender-based conventions of dress are enduring. Items of clothing like the hijab are still politicised as a result of the continuation of colonialist attitudes and islamophobia. Women who wear hijabs are often mislabelled as “oppressed”, or seen as anti-Western society.

Pink Pussy hats worn at Women’s Marches over the past few years have received a lot of attention…but not entirely positive. Source: Unsplash

As such, fashion is not frivolous. For marginalised people in particular, clothing and style choices are interwoven into identity politics, whether the wearers like it or not. We often assume that we can use a person’s style choices as a barometer for measuring the degree to which they accept or reject existing power hierarchies or certain political ideologies.

We see that women, in particular, are expected to use their clothes to say something about themselves. In 2018, a conference hosted by Yale University to help US women run for office included a two-hour session entitled “Dress to Win”, which encouraged women to use their clothes to grab attention and “project..what you believe”. As reported in the New York Times, lecturer Sonya Gavankar said:

“When you put on the black suit and the patriotic scarf, that does not tell people to pay attention…It’s not going to inspire people to want to hear what you say…Let the men be boring.”

The expectation that women should use fashion to communicate their politics ultimately makes fashion an unwelcome distraction in the pursuit of gender equality. Firstly, on an individual level, women are expected to invest far more time and money in dressing than men are – all time and money which is diverted away from the pursuit of a woman’s primary goals. Furthermore, for less-wealthy and plus-size women (who have far fewer clothing options available to them), clothing can become a major barrier to their success. The intense scrutiny we put women’s outfits under inevitably diverts the public’s attention away from women’s voices and towards their bodies.

For some people, clothing choices can be liberating. Through the resurgence of politically-branded clothing, women are reclaiming fashion as an instrument of change. However, where fashion and politics intersect, empowerment is not always the outcome. We expect to be able to make assumptions about marginalised peoples’ political views based exclusively on their clothing, even in the absence of political branding. By placing such high expectations on appearances, we perpetuate a consumeristic culture - identity is relocated to what we have rather than who we are. Clothing should be seen as an optional facet of identity politics; clothes can speak with us, but they no longer need to speak for us.