By Syaa Liesch (they/them)

Content Warning: discussions of colonisation and racism

My issue is that people like to stereotype black Muslims as angry militants who did jail time and left behind a life of crime and violence. The more typical story is [that] an indigenous people was searching for a spiritual way and found Islam to be incredibly liberating.

-Eugenia Flynn, a former Catholic who declares Aboriginality as her culture and Islam as her faith (quoted in Morris 2007, 9).

I’d like to begin by acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land on which I am writing this piece. I would also like to pay my respects to Elders past and present.

Through my research into this topic, I have done my best to foreground Indigenous voices and history, and I hope that I am able to accurately reflect their understandings.

This is only a brief history of Islam’s influence on Indigenous spirituality. Out of the vast interactions between Indigenous Australia and Islam, this article will focus specifically on two historical points of contact, the Makassan trepangers and the Afghan cameleers, as well as the modern cultural impact.

While researching, I was constantly reflecting on my own experiences surrounding the teachings of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander’s beliefs, particularly in high school. White teachers, with little to no real understanding of First Nation’s beliefs, were unable to convey the complexity and diversity of Indigenous cultures. While I was shown the Indigenous map of Australia, highlighting the different communities and language groups across Indigenous Australia, I wasn’t educated on different cultural traditions, and Indigenous people were portrayed as a homogenous group. Especially now, post colonisation, where religion is no longer limited to a particular culture or location and Christianity has been recognised as a significant aspect of colonisation, I believe it is extremely important to learn about the multiplicity of beliefs both between and within Indigenous Australian cultures.

The Australian Census data from 2001-2006 has shown that Muslim conversion in Indigenous communities has increased by 60% (Stephenson 2011). However, even this term ‘conversion’ is problematic, as it implies the complete change from one religion to another. In reality, people often have complex identities made up of many intersecting elements.

Makassan trepangers: Influence through trade

Islam’s presence in Australia preceded colonisation. While different accounts describe contact as early as the 8th and 10th centuries, reliable records from the 1700s document the ‘Makassan’ trepangers; Indonesian fishermen annually visiting the north and north-western coastline of Australia to search for trepangs (sea slugs) before heading north to China. Despite the term ‘Makassan’, the fishing fleets were comprised of ethnically diverse crews from around Indonesia, including people from Makassar, Bugis, Java, and Ceram among others (Clarke 2000, 317). It has been established that a relationship and dialogue existed between the Muslim fishermen and the Yolŋu peoples of North-Eastern Arnhem Country, part of what is now called the Northern Territory (Ganter 2008, 483).

As Australian Indigenous people have strict protocols regarding access to Country, it is likely that there was a treaty in place, with the fishermen living in accordance with the principles of Indigenous law (Sneddon 2020, 73). There is evidence that the Makassans negotiated for the right to fish in Aboriginal waters and paid wages to the local Aboriginal people, supplying various goods such as tobacco, rice, gin, knives, and sometimes entire canoes (Russell 2004, 8). Through this daily contact, the Yolŋu people became aware of Islamic rites such as daily prayer and burial practices as Muslim prayer-men accompanied the fishermen. Observations of Islamic rituals, such as Yolŋu women praying to the sunset and invoking the name Allah, and ceremonies where mantras are sung that can be translated from Arabic, demonstrate the absorption of some practices into local customs (Sneddon 2020, 77). Their belief in the Dreaming creation figure Walitha’walitha (adapted from the phrase ‘Allah ta’ala’ meaning ‘God, the exalted’) confirms the religious legacy of the Makassans. The now past leader of the Warramirri clan explained that after the Aboriginal people turned their back on the law of the mythical being Birrinydji, the wurramu, an evil spirit, entered their lives. Walitha’walitha came down to Earth to restore peace. In his words: ‘Yolŋu have two bosses, Birrinydji and Walitha’walitha. Each limits the other. Walitha’walitha is Allah. He dwells on top ... Walitha’walitha tells us of right and wrong. It’s sort of a sixth sense. It can judge a situation’ (Burramurra quoted in McIntosh 1996, 63). While there is an overlap in the Yolŋu and Islamic understandings of Allah, they are also quite separate, with Walitha’walitha being an Aboriginal creation associated with particular Aboriginal clans. As such, while the Yolŋu never embraced Islam as a faith, Islam began to influence their belief, with certain elements being incorporated into their cosmology.

Afghan cameleers: The first Muslim settlers

Since its colonisation of Australia, the British Empire has had a direct influence on both the Indigenous peoples of Australia and immigrants. The first Muslims to permanently settle in Australia were the ‘Afghan’ cameleers, members of nomadic clans who travelled around what is now Afghanistan and Northern India. They were brought to Central Australia by the British colonists during the 19th Century, importing camels and creating tracks that linked together towns, mines, stations and missions around the outback (Abdalla 2012, 9-10). These tracks often followed older Aboriginal migratory pathways, which brought them into contact with a variety of Aboriginal cultures. The cameleers rebuilt their lives alongside the Aboriginal social environment whilst continuing to dress in their traditional clothes and maintaining their devout practices of Islam in Australia. They created makeshift mosques alongside their camps throughout the outback. Despite the contributions the cameleers brought to society, their ethnicity placed them as second-class in the eyes of white, European, Christian Australians and they were alienated from society (Sherin 2012, 29). This only grew with the implementation of the Immigration Restriction Act (1901-1958) – the ‘White Australia Policy’. Social restrictions were placed on Muslims, regulating halal butchers, camel grazing, and their use of public highways. The cameleers, viewed as inferior and debased, had their movement controlled in order to prevent the ‘spread’ of their population (Abdalla 2010, 10-11).

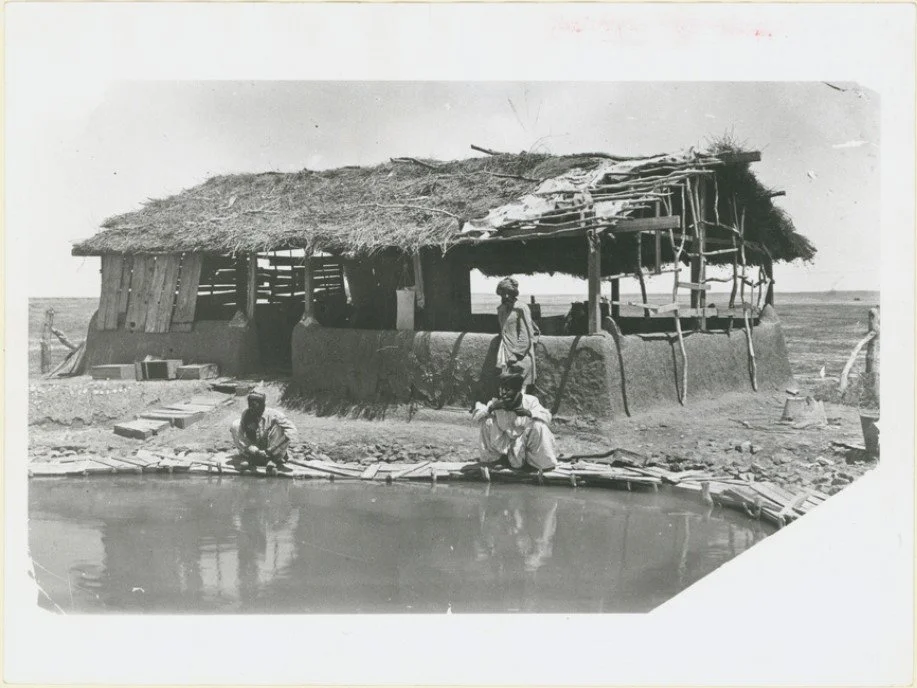

Black and white image of Marree Mosque in South Australia, the first Mosque to be built in Australia. Source: State Library of South Australia, The Mosque, Marree [B 15341] • Photograph, no copyright restrictions

These restrictions increased tensions and discrimination within communities, pushing the cameleers and their mosques to the fringes of society, away from White towns. It was in these spaces where they came into close contact with local Indigenous tribes, due in large part to the mistrust and mistreatment of anyone who white people considered to be ‘other’ (Onnudottir 2013, 52).

This facilitated both short-term and long-term relationships between Afghan cameleers and Aboriginal women. Through contact and the subsequent discovery of shared social practices, cultural traits, and experiences, such as acclimatisation to the heat, shared similar experiences of resistance to invasion, and respect towards elders (Rahman 1987, 303), they exchanged skills, knowledge, and goods (Stephenson 2010, 44). Even after the removal of many cameleers through the White Australia Policy, Central Desert people continued to use camels for decades, both for practical and theatrical uses. Camels held major importance, acting as links to Afghan ancestors and Islam, founding a symbolic and material reality in the minds of Indigenous people (Onnudottir 2013, 53). Today, there are many Aboriginal families with Afghan surnames, such as Khan, Sultan, Mohomed, and Akbar. After marrying an Afghan cameleer, these Aboriginal wives would move into Afghan communities and followed the Islamic lifestyle and codes of behaviour. As they did not set aside areas for women, the wives did not attend the daily prayer periods, however, they prepared halal meals, dressed modestly, and did not leave home without either a chaperone or their husband. As such, while these Aboriginal wives embraced everyday Islamic practices they did not adopt an Islamic theology, maintaining a connection to their Indigenous spiritual beliefs (Stephenson 2013, 431). While practices and beliefs within these families have changed over the generations, many Indigenous-Muslim descendants today are still part of close-knit communities, sharing affinity through common backgrounds, both of Aboriginality and Muslim understanding (Stephenson 2010, 62-68).

‘Kinverts’: Indigenous and Muslim identification

For many Indigenous-Muslim descendants, self-identification has very little to do with religion. Instead, identification as Muslim is primarily an expression of kinship, or Muslim background. Rather than firmly embracing the principles of Islam, they largely turn towards their family history and the act of respecting the memory of their ancestors. The term ‘kinvert’ was coined by Peta Stevenson who describes it as ‘an Indigenous connection to Islam that is culturally – usually family or kin – based … [that] does not involve the active acceptance of, or even any great acquaintance with Islamic doctrine’ (2013, 432).

The analysis of the historical contact between Indigenous Australians and Makassan and Afghan Muslims highlights the role of white oppression in encouraging cross-cultural alliances. The shared experience of resisting colonial control resulted in shared political strategies of resistance, which continues today as political resistance to Westernisation and assimilation. Practicing Islam can be an act of self-empowerment, as people awaken personal histories and begin to express their identity outside the context of whiteness and colonialism. Islam can act as an integrating factor to the Aboriginal identity (Stephenson 2005, 84-87).

Furthermore, the cultural similarities between Muslim and Aboriginal communities helps strengthen their identification, as many believe that ‘going back’ to Islam is also simultaneously ‘going back’ to their Indigenous roots. Some Indigenous women feel connected with their Aboriginality through Islam due to the shared emphasis on gender roles. The clear roles attributed to men and women in Islam are comforting in its similarity to Aboriginal life. The two also have similar attitudes to the environment: both the Qur’an and the Aboriginal elders clearly say to not waste what is not needed, emphasising nature as precious. Aspects of community, too, are familiar, as elders are held in high esteem in both Islamic and traditional Indigenous societies. Many believe that Islam parallels Aboriginality’s sense of community mindedness, unlike the ‘Western way’ that is normalised in White Australia (Stephenson 2013, 435).

As such, Islam does not only appeal because of the cultural overlap, but because it represents an alternative faith and lifestyle to that of their oppressors. Research surrounding Islam’s empowerment of Indigenous Australians envisages a continued growth of the Indigenous Muslim population, as Islam meets both spiritual and social needs: their identification offers a ‘buffer against systemic racism, a clear moral template, well-defined roles and entry to a global society that does not make assimilation the price of admission’ (Stephenson, 2011). One interviewee from this study stated that ‘Islam doesn’t just say you’re Muslim, that’s it. It recognises we belong to different tribes and nations. So, it doesn’t do what Christianity did to a lot of Aboriginal people, [which] was try and make them like white people’ (Stephenson, 2011). The growth of the Indigenous Muslim population is not just due to cultural similarities and ancestral roots helping to strengthen their identification with both Muslim and Aboriginal communities; it is a step towards a spirituality that resists White, colonial logics.