Are women the targets of self-care?

By Bridget Gibbs (she/they)

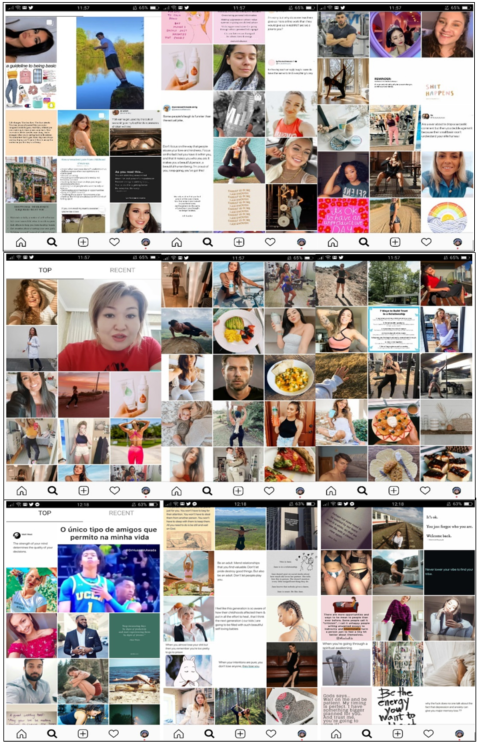

Do women see more of ourselves depicted in self-care imagery? I performed a quick experiment which confirmed my suspicions that feminine appearing traits and users would largely dominate top tagged posts for ‘self-care’, ‘wellness’, and ‘mindfulness’ on Instagram. To do this, I searched for these tags and screenshotted the results below. At first, I wondered whether a larger majority of Instagram users had their gender set as ‘female’ and if this could bias the results. There is a slightly higher number of ‘female’ users (56.4%) than those set to ‘male’ (43.6%) in Australia (Pokrop 2020), but I do not think this had an immense impact on the results.

It is important to note that I have made a couple of assumptions here. The first is that I am assuming that all of the users with their gender set as ‘female’ do in fact identify as female, as opposed to identifying as neither female nor male in which they would use the ‘custom’ gender option. I have also used the terms ‘feminine-appearing posts’, and ‘masculine-appearing posts’ here which refer to the images I personally think appear related to feminine or masculine traits. These terms relate to traits that are traditionally associated with women and men respectively. However, these terms have different definitions and meanings to different individuals so I encourage you to perform your own mini experiment and find the top posts on your device, using the same tags I did!

Top five rows: top tagged posts for “self-care”. Feminine-appearing posts: 16, masculine-appearing posts: 2, other: 24.

Middle five rows: top tagged posts for “wellness”. Feminine-appearing posts: 26, masculine-appearing posts: 2, other: 11.

Bottom five rows: top tagged posts for “mindfulness”. Feminine-appearing posts: 21, masculine-appearing posts: 1, other: 20.

All screenshots were taken on my phone on the 24th April 2020.

What are the consequences of feeling bombarded by self-care imagery and advertisements? Do women inherently feel more burnout as a result?

It feels like I have become more and more exposed to online posts that are confusingly attached to this particular set of personal-care language and imagery. I am familiar with this terminology in different contexts, and I thought I had a fair understanding of what it means to do self-care and similar activities. The search results for self-care portray a somewhat expected group of images: gym-aesthetics, selfies in the sun, a few products and a scattering of life quotes. Yet none of these images really help me to decipher my relationship to self-care, or reflect my own set of personal-care activities. A look at the wellness category shows a few more mixed messages. Does wellness relate to eating breakfast foods? Does it mean working out? Or does it mean taking photos of ourselves holding up products? Perhaps it is all of these things? The majority of images come from feminine-presenting users. Finally, a glance over the mindfulness top posts does not help me to find clarity. Does mindfulness relate to doing yoga? Does it relate to body positivity? Or to picking grapes? There are a variety of images here and again, the majority are from feminine-presenting users.

Although my results show a very small sample size and are by no means definitive, it confirms for me that those I consider to be feminine-appearing users, are heavily portrayed in self-care practice and imagery. I would hazard a guess that a number of these users are trying to sell me something, or have been paid to flaunt their wellness, their self-care routines, or their mental health care strategies. For me, the obvious consequence of being bombarded with ads and images labelled as self-care, which I do not recognise as self-care, is that I compare these images to my own life. It is at this point that those burnt-out feelings start to resurface. I have noticed how easy it is for me to go against my better judgement and buy into other people’s versions of self-care. So, as with most things in life, the responsibility falls to us as the consumers of these images to sift out the ones that are clearly trying to profit from our well-intentioned interests in performing self-care.

Perhaps there is something more profound occurring here. It feels as though these self-care (and similar) labels are actively reinforcing gendered stereotypes. Specifically, these labels might emphasise traits like being caring and nurturing (towards yourself and towards others), which are so often associated with women. In my own experience living as a young woman, I have had these caring and nurturing associations attached to me in various workplaces and in my home life. Even during the initial stages of our current pandemic, I noticed an increased expectation on the women around me to check in on colleagues and family members. Why does this task fall to women?

It is interesting to me that these caring behaviours are reproduced in personal-care and wellbeing imagery online. The major issues I have with this, is that it reinforces a limited view of what self-care is, of who mainly performs it, and of how self-care should be achieved. For those of us who cannot relate to the Instagram marketplace version of self-care (and dare I say the female-oriented, whitewashed version), it might be easier to slip into negative thinking around the subject. This limited self-care imagery also potentially excludes other groups from participating in self-care and similar activities, if they cannot see themselves reflected in these images.

Positivity and helpful practices without the stress of ‘doing self-care’.

How can we limit the clouds of stress associated with performing self-care? (Sarah Ayoub 2019)

I decided against providing a list of suggestions for self-care activities, as the things that work for me might not work for you. For most people, simply deleting our social media is not a long-term strategy, and I don’t recommend throwing out your current self-care practices altogether (if you have any). So here are a few ways that we can limit the clouds of stress that can be associated with doing self-care:

1. Re-consider what self-care actually means to you. The whole concept of self-care seems to be widely misinterpreted. We cannot solely rely on quick fixes and self-soothing approaches if it means we are not carefully considering the origins of our troubles. Practicing self-care and attending to our wellness is an active process which also involves doing things that we might not want to do. It is also helpful to remember that health can be understood as mental, physical, emotional, spiritual, social, and/or environmental.

2. Another important step is to constantly remind ourselves that the things we see online (ie. Instagram) are not always published in good faith. Many individuals and companies behind the scenes want us to buy something, even those products and services targeted at self-care.

a. Try not to make impulse buys from Instagram, although many of us are guilty of this. If you do not already perform the activity that this new product might enhance, search instead for a free or trial option, or for a person with knowledge of the subject before making any quick buys.

3. When we see information about self-care and wellness online and we have a “I need to do that,” or a “I should be doing that more often” moment, we should take the time to remember that all people find peace in doing very different things. It may some trial and error before you find the practices that benefit you.

4. Think of self-care as more than just individual or self-benefitting action. A collective or community action, rather than an individual action might benefit you if caring for others is already part of your self-care practice.

a. I have recently been taking part in webinars and Q and A sessions on a range of subjects, and these have shown me how the world of activism continues to move forward, even during this time of crisis. These sessions have also reinforced that collective goals can be just as powerful as individual goals. In a webinar hosted by the University of Queensland’s School of Psychology (watch here), Professor Alex Haslam describes how “social connections are incredibly important for our health and our wellbeing but we really really take them for granted… but social connection is one of, if not the most important determinant of health”.

b. If you haven’t already, reflect on how you might connect with people online who have similar interests. Consider how you can recreate the in-person connections and things that you are passionate about in the form of virtual group thinking or collective action. A helpful way to recognise the groups you are already a part of and to organise these in terms of priority, is with a UQ-lead site called Groups2Connect (found here). If you already have multiple online groups to connect with, this tool might be useful to see how you might interact with them more (or less) in your isolation time. Professor Haslam reminds us again, that “group based links have a particular value… we are always able to bring something of ourselves to every situation we find ourselves in, but… it is a whole lot easier to do that if we can find someone else to do it with” (watch the full-length Q and A here).

If you would like to discuss anything mentioned here please don’t hesitate to send me a message at b.gibbs@onewomanproject.org, or connect with the wonderful OWP Team on Facebook and Instagram (‘One Woman Project’).

Reading List + References

Ayoub, Sarah 2019, ‘I can’t explain millennial burnout to my mother’, SBS, https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/voices/culture/article/2019/04/08/i-cant-explain-millennial-burnout-my-mother

Dean, Tim 2015, ‘Does pursuing health make us less happy?’, New Philosopher, vol. 7, pp. 84-87.

Goop, Rose quartz crystal straw, https://shop.goop.com/shop/products/rose-quartz-crystal-straw?country=USA

Gormley, Elena 2019, ‘Anti-Semitism is the Reason for My Millennial Burnout’, alma, https://www.heyalma.com/anti-semitism-is-the-reason-for-my-millennial-burnout/

Havlin, Laura 2019, ‘Is your self-care practice fuelling your burnout?’, Dazed Beauty, https://www.dazeddigital.com/beauty/soul/article/44713/1/self-care-practice-fuelling-burnout-capitalism

Human Psychology 2020, ‘Self-care is not taking a nice bath’, https://humanpsychology.com.au/self-care-is-not-taking-a-nice-bath/

Perissinotto, Kristin 2020, RARA Magazine, ‘Self care in the digital age’, One Woman Project, https://www.onewomanproject.org/shop/rara1

Prokop, Jan 2020, Instagram user demographics in Australia- March 202 UPDATE, NapoleonCat, https://napoleoncat.com/blog/instagram-users-in-australia/

Ruiz, Rebecca 2019, ‘Our best bet against burnout is self-care, just not the kind you think’, Mashable, https://mashable.com/article/burnout-treatment/

Sekaram, Sharanya 2018, ‘The politics of self care and femininsm’, GenderIT.ORG, https://www.genderit.org/feminist-talk/politics-self-care-and-feminism

Sonnentag, S 2003, ‘Recovery, Work Engagement, and Proactive Behavior: A New Look at the Interface Between Nonwork and Work’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 88, no. 3, pp. 518-528.

The Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkely 2020, ‘What is mindfulness?’, https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/topic/mindfulness/definition

University of California, Davis, ‘What is wellness?’, https://shcs.ucdavis.edu/wellness/what-is-wellness

University of Queensland Art Museum 2020, ‘We need to talk about…Self-care in times of extreme stress’, https://www.facebook.com/uqartmuseum/posts/3600368293322868

University of Queensland 2018, ‘Groups2Connect’, https://uqpsych.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_cVoO38bnfl8x8YB?source=uqpsych&Q_JFE=qdg

World Health Organization (WHO) 2020, ‘Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases’, https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/